Strategies for Gentle Densification of Cleveland Park, Woodley Park, and Van Ness, DC

A Capstone Proposal By Harrison “Mac” Hyde, Master of Urban and Regional Planning Program, L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University, Fall 2023

Introduction

This study seeks to create a plan for the densification of the residential areas surrounding the Cleveland Park, Woodley Park, and Van Ness Metro stations and will be conducted with the assistance of Cleveland Park Smart Growth (CPSG), represented by one of the co-Founders, Bob Ward, in Washington, D.C. Collectively, Cleveland Park, Woodley Park, Van Ness, and Forest Hills are part of a subset of DC known as Rock Creek West. The densification of these areas will be achieved by introducing “gentle” density, typically defined as attached townhouses and small multifamily buildings that do not appear out of place in single-family neighborhoods, both through proposed zoning changes and by proposing design guidelines for the study area (Baca et al., 2019; Rojc, 2017). The community will be consulted extensively on all proposed changes and guidelines as well as share in the findings. The tangible outcomes of this study will be: a set of design guidelines, proposed changes to the Zoning Code of 2016, and an analysis of the co-benefits of densification. The co-benefits analysis will examine any potential changes in tax revenue for the city, potential ridership changes for the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA), as well as changes in the potential customer bases for local businesses in each neighborhood. These analyses will be done for a maximum build-out Scenario A, a less dense Scenario B, and a do-nothing Scenario C. The ultimate goal of introducing gentle density to the study area is to increase the supply of affordable housing across all income levels, defined here as housing that costs no more than 30% of an individual’s income, decrease racial segregation within the city, promote equity, provide a larger local market for neighborhood businesses, allow community members to downsize/age in place, increase transit ridership, and increase sustainability.

With a housing shortage of 134,000 units, one that continues to grow every day, the District has begun to consider in earnest the impact single-family zoning has on housing affordability and other metrics (Divounguy, 2023; Housing Shortage Tracker, 2020). Currently, 59% of all residential land in the District is zoned for single-family residential. Of that 59%, 36% is for single-family detached, with the rest going to single-family attached or semi-detached (Single Family Zoning in the District of Columbia, 2020, p. 6). Much of the land set aside for single-family detached housing coincides with the three highest grades of land in the 1937 Federal Housing Administration Map. In turn, highly graded lands were “protected” through the use of deed covenants and discriminatory lending practices to ensure a segregated populace. To this day, many of the neighborhoods which largely consist of single-family homes are more racially segregated than of areas of the city (Single Family Zoning in the District of Columbia, 2020, p. 17). Of the housing in Rock Creek West, 40% of rental units in the area are deemed affordable, with only 1% dedicated to affordable housing. Unsurprisingly, a higher proportion of extremely low-income (<30% Median Family Income (MFI)) to moderate (80-120% MFI) residents in Rock Creek West report feeling burdened or severely burdened by housing costs compared to the rest of the city (Rock Creek West Roadmap, 2021, p. 9).

One of the many barriers Cleveland Park Smart Growth identified to introducing “gentle density” was a perceived reticence in the community to allowing more units into the neighborhoods. This can potentially be overcome in a variety of ways, from ensuring that the development matches the existing neighborhood context to altering the wording of a proposal to be more positive (Pfeiffer, 2015, p. 282; Whittemore & BenDor, 2019, pp. 1362–1364). One key aspect of densification my partners in CPSG would like to explore is how some types of secondary units, namely Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), are adept at housing residents in a variety of life stages, from early adulthood through to retirement age (Nichols & Adams, 2013, p. 43). CPSG views this as a potential swaying point for many community members who wish to age in place.

One of the benefits the study will investigate is the relationship between density and environmental sustainability as sustainability is positively related to density (Dunning et al., 2020, p. 305). This study will also explore the relationship between density and transit usage, which, much like sustainability, is both positively perceived and correlated (Kenworthy & Laube, 1999, p. 719). This study will quantify these relationships, in a local context, in order to bolster the argument for gentle density.

Literature Review:

As the United States continues to grapple with a housing shortage, planners have increasingly been looking to neighborhood densification to boost housing production, rein in prices, and meet sustainability goals. Residential densification can take many forms, from the construction of multiple, smaller units where a large single-family residence once stood, to the addition of either an internal or external ADU, to the conversion of a single-family residence into multiple units within the original structure. This literature review will focus on the latter two types of neighborhood densification as many of the additional housing units we are seeking to add to the study area would be in the form of either an ADU or single-family residence conversion. While accessory dwelling units can be built in all shapes and sizes, ranging from fully independent structures to converted floors of a residence, they have one significant characteristic in common; they are built and function as independent living units (Accessory Dwelling Units, n.d.). Much of the academic literature surrounding infill housing focuses on the effects of ADUs in specific cities or what policies can enable or limit ADU construction. There are fewer papers that attempt to generalize the effect of ADUs on their host communities. Similarly, research focusing on neighborhood opposition to increased density or housing developments, often referred to as Not in My Backyard-ism, or NIMBYism, focuses on the potential motivations behind such behaviors and less on potential solutions to such thinking. Nevertheless, this literature review shall endeavor to convey the various benefits of residential densification as well as why neighborhoods might oppose such developments and what, if anything, can be done about that opposition.

While there are valid concerns to allay, the benefits of neighborhood densification far outweigh the costs. The benefits of densification are often intertwined, but they broadly fit into three categories: environmental, social, and economic.

The environmental benefits of densification are numerous, but they all stem from one concept; living more densely can influence residents’ lifestyles. Typically, a denser neighborhood promotes walkability as well as increased utilization of transit, leading to fewer carbon emissions. This is due to several factors; as neighborhoods become denser, they often attract car-sharing services, thus allowing households to go car free. In doing so, households typically drive less than if they owned a car. Denser neighborhoods can lead to increased transit service, or at the very least, increased ridership on transit lines that already exist by increasing the number of people a route can potentially serve (Morales, 2018a, 2018b). This, in turn, can improve air quality, provided that the densification occurs in urban areas already served by transit or will soon do so (Stone et al., 2007). Oftentimes, ADUs and other secondary units are smaller than an existing single-family home in the area. This leads to a more efficient use of space, and more importantly, a decrease in the amount of energy needed to maintain the smaller dwellings, allowing each unit to have substantially lower emissions (Andersen, 2019).

Denser neighborhoods often provide economic benefits as well, usually in the form of increased patronage of local shops and businesses, as there are more people within walking distance of a business. Increased density makes a neighborhood more attractive for businesses, allowing them to be supported within a smaller geographical area (Baca et al., 2019; Morales, 2018b).

Densification can also yield social benefits. When coupled with requirements for affordable housing or other forms for housing assistance, increasing the housing density of neighborhoods helps bring traditionally high priced, high amenity neighborhoods within reach lower income homeowners and renters (Andersen, 2019; Kim, 2016). Allowing homeowners to build ADUs can help them age in place, either allowing them to downsize into the ADU itself or rent the ADU to generate additional income (Lehning, 2012). ADUs can foster multi-generation households while permitting greater independence for all members, ensuring that the elderly have safe spaces to live while staying close to their communities and families (Baron Pollak, 1994). These spaces are not exclusively reserved for the elderly, however. They can be used by anyone of any age. In some communities, ADUs have been used by adult children returning home, allowing them to improve their finances while maintaining their independence (Nichols & Adams, 2013).

Urban development in the United States has been an uphill battle for many years. For decades, urban planning journals have written about how opposition, often referred to as NIMBYism to locally unwanted land uses (LULUs) have stymied the siting and construction of critical city facilities (Dear, 1992). This naturally extends to the development of housing, with many groups opposing increased housing production for a variety of reasons. One of the most common refrains is that increasing housing production within a neighborhood will lead to a destruction of the qualities that make a neighborhood desirable either by diminishing aesthetic qualities or reducing the ability for residents to enjoy neighborhood amenities, such as plentiful parking (Doberstein et al., 2016; Dunning et al., 2020; Ellickson, 2020; Holleran, 2021; Manville et al., 2020). A powerful motivation behind NIMBYism is the protection of property values. Many residents fear that the value of their single largest asset will decline if denser housing, especially housing that’s been designated as affordable, were built (Ellickson, 2020; Holleran, 2021; Wicki & Kaufmann, 2022). When affordable housing is proposed, this fear often expands to include the perception that the incoming residents and thus the development that allows them to move into the neighborhood will be a source of economic, social, and environmental degradation (Scally & Koenig, 2012). One aspect of NIMBYism that can be more readily addressed is that of design quality, with opposition often focusing on the low quality of some designs. Conversely, when blighted local properties are repurposed in creative ways, there is more often local support for projects (Dunning et al., 2020).

There are several methods for overcoming NIMBY opposition. Most notable among them are top-down interventions, such as Governor Gavin Newsom’s effective ending of single-family zoning in California in 2021 (Healey & Ballinger, 2021). While these reforms effectively go around local NIMBY opposition, they require the support and backing of a state legislature and governor as well as at least tacit endorsement from the electorate; a tall order for any reform.

There are a few, less heavy-handed approaches to win over local communities. It has been shown that when a project includes construction of neighborhood amenities, such as improved parks or expanded public transit service facilities, communities are more likely to support a project (Ellickson, 2020; Wicki & Kaufmann, 2022).

Another method for overcoming NIMBYism is to invite the community to participate in the project or organization, oftentimes by appointing an advisory board consisting of community members. Not only will decision makers gain useful knowledge and insight from the hyperlocal experiences of residents, but advisory boards can potentially convert opponents into proponents (Dear, 1992).

The most widely reported method of overcoming NIMBYism, with a few variations, is that of framing the proposed zoning changes or development in such a way as to focus on the benefits for neighborhood residents. For example, benefits from a change in zoning rules can include: allowing residents to age in place, improving environmental stewardship, or bettering public health (Dear, 1992; Doberstein et al., 2016; Pfeiffer, 2015). While this method varies in effectiveness depending on several factors, including existing neighborhood morphology, it can be effective in widening resident’s perceptions and allay concerns about property values, traffic, or other issues (Whittemore & BenDor, 2019).

While not an outright method of negating NIMBYism, it has been suggested by some (Vall-Casas et al., 2016), that the benefits of densification can be best realized if regions work to systemically densify as opposed to the ad hoc method prevalent today. Doing so, Vall-Casas et al. argue, allows localities to invest in larger scale adaptations to density and ultimately deliver greater benefits to residents.

Existing Conditions:

Study Extent

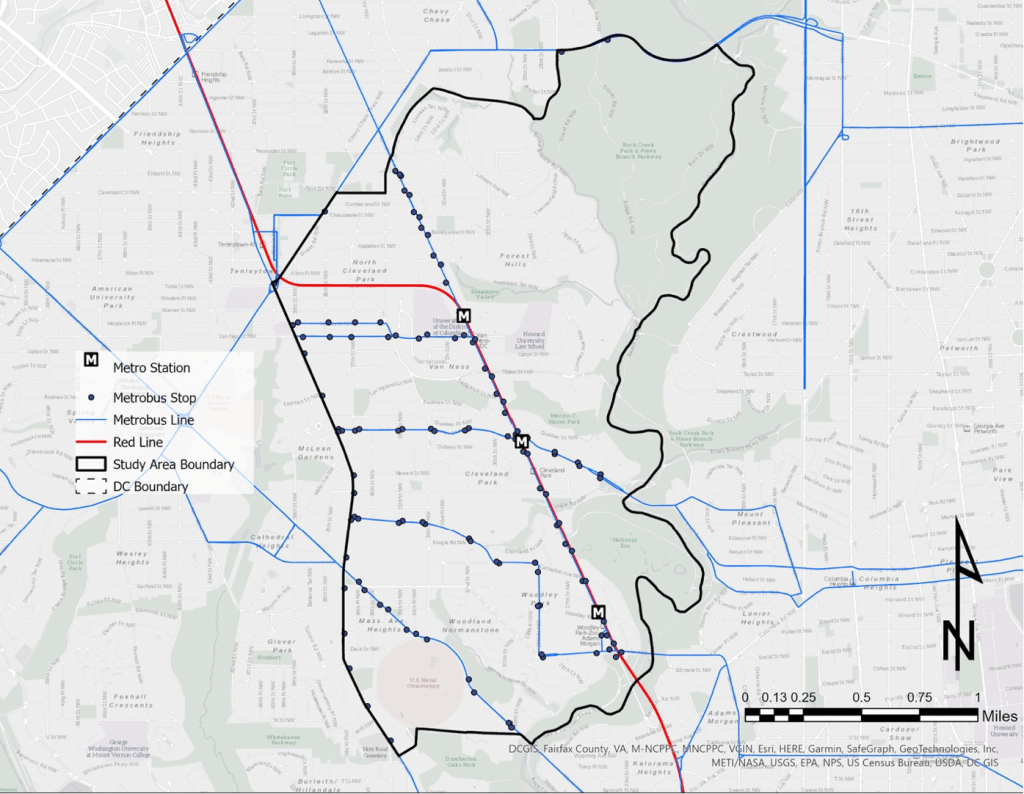

The study area covers 12 census tracts, comprising the portions of six DC neighborhoods: Woodland Normanstone, Woodley Park, Cleveland Park, Van Ness, and Forest Hills (See Figure 1). The study area is bounded by Rock Creek Park to the east and south, Nebraska Avenue NW to the north, and Wisconsin Avenue NW to the west. These 12 tracts were selected due to their proximity to the Woodley Park, Cleveland Park, and Van Ness Metrorail stations. Portions of all tracts fall within the ½ mile distance most people are willing to walk to access high quality transit (Federal Highway Administration, 2013).

Figure 1: Study Area Extent

Neighborhood Composition

The study area is largely residential in character, with neighborhoods centered on commercial corridors running along Connecticut Avenue. The housing stock consists largely of single-family detached homes, with most multifamily buildings concentrated along Connecticut Avenue. There are a few multifamily buildings scattered throughout the study area, but construction of such buildings has been largely illegal since the 1920s (Ward, 2022).

Transit

The study area has excellent transit connections to the rest of the region via Metrorail’s Red Line and Metrobus lines H2, H4, L2, and 96 (See Figure 2). Within the study area, the Red Line stops in Woodley Park-Zoo-Adams Morgan, Cleveland Park, and Van Ness-UDC, and from there continues north to Shady Grove, MD or south to Downtown where it connects with the rest of the Metrorail system before eventually turning northeast to run to Glenmont, MD. Metrobus route L2, which is the Connecticut Avenue Line, run from Chevy Chase to Downtown via Connecticut Avenue, while the 96, also known as the East Capitol St.- Cardozo Line, and H2/H4, known as the Crosstown Line, provide the crosstown access. Only the Crosstown Line, however is considered to have frequent service (Metrobus System Map, 2022).

Figure 2: Transit of the Study Area

Amenities

Peppered with parks, high-quality schools, and easy access to fresh food, the study area is a prime example of a high resource neighborhood (See Figure 3; Affordable Housing in Opportunity Areas or Resource-Rich Neighborhoods, n.d.). There are numerous parks, from the large, mostly natural, Rock Creek National Park, to small neighborhood playgrounds and recreation centers such as Macomb Recreation Center. The study area’s public schools, most of which are newly rebuilt, are among the best in the city, ranking either 4 or 5 stars on the city’s school ranking system, with many other highly ranked schools nearby. There is an abundance of fresh food available as well, with the study area boasting four separate farmers markets, six grocery stores, and four additional grocery stores within a short distance of the study area boundaries.

Figure 3: Amenities within the Study Area

Historical

As the study area is an amalgamation of several different neighborhoods, each with their own unique history and pattern of development, it is difficult to write a single, definitive history for the study area. The neighborhoods do have a few things in common, however. Development began in earnest after Rock Creek Valley was bridged in the late 19th century and the streetcar could be extended up Connecticut Avenue (Alexander & Williams, 2004; “Connecticut Avenue Highlands” | The Cleveland Park Historical Society, 2011). As the area developed, many properties were placed under racial covenants, preventing their sale or occupation by anyone other than White Christian individuals, with the exception of Forest Hills (Cherkasky et al., n.d.; Reinink, 2012). Some neighborhoods, notably Cleveland Park, instituted a floor on sales prices in an effort to price out large swaths of the population. In a few cases, neighborhoods went even further, banning the construction of apartment buildings, claiming them sources of immoral behavior, further restricting the availability of affordable or attainable housing (“Decision on Naming ‘A Restricted’ Area in Zoning Deferred,” 1923; Ward, 2022).

Policy

As is the case in almost any large urban area, there are many different policies that influence and govern what can currently be built within the study area (See Figure 4). The policies that will have the largest bearing on this project are zoning designations and historic district regulations. The current zoning designations for the study area places an emphasis on residential uses, with every zoning designation being able to accommodate some form of residential housing. However, over 70% of all zoned land is reserved for single-family detached homes. The remaining land is split between mixed-use, apartment, and single-family attached zones (Zoning Regulations of 2016 (Unofficial Version), 2016). While not necessarily impacting the zoning of residential areas, it is worth noting that the District is planning to up-zone the commercial corridors of Cleveland Park and Woodley Park to allow for greater density in the pre-existing mixed use zones, including within historic districts, with an eye towards building more housing, both market rate and affordable (Connecticut Avenue Development Guidelines: Draft April 2023, 2023). Comprising several neighborhoods that are representative of notable periods in the District’s history, the study area encompasses more than one historic district. The two principle historic districts within the study area are the Woodley Park Historic District and the Cleveland Park Historic District. Both are governed by the District’s Historic Landmark and Historic District Protection Act of 1978 which grants the Historic Preservation Review Board or Commission of Fine Arts the authority to review any proposed project within a historic district and ensure its compatibility (Historic Landmark and Historic District Protection Act of 1978: (D.C. Law 2-144, as Amended through March 1, 2020), 1979).

Figure 4: Zoning and Historic Districts of the Study Area

Methods

The study will be divided into four components: an initial survey, the creation of design alternatives, public engagement, and a GIS analysis. All components of research will be guided by five central research questions (See Table 1).

Table 1: Central Research Questions

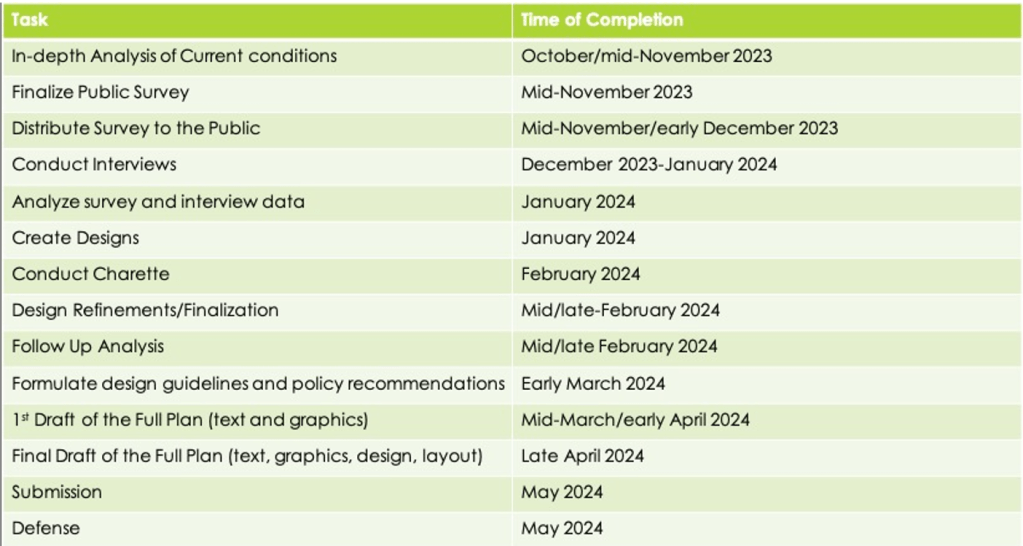

The first step of the study will be to conduct a survey to establish a baseline of community attitudes toward density, what objections they might have to increasing density in residential areas, and certain pieces of demographic information, such as size of household (See Appendix A). This will be coupled with an analysis for census data to create both potential design alternatives as well as shape supporting arguments for increasing residential density. Informal interviews will also be conducted with local planning professionals, politicians, and land use experts to determine what types of densification are possible under the current policy regime for the study area. Following analysis of the survey, Census, and interview data, initial design alternatives will be created using SketchUp. Charrettes will then be conducted to elicit feedback from the community and identify any improvements that could be made to the design and policy recommendations. Once a design and policy solution has been identified, a GIS analysis, using ArcGIS Pro, will be conducted to simulate various levels of buildout to bolster arguments for densification. The data collection using the proposed methods will be completed over the course of eight months according to the Schedule of Competition in Table 2.

Table 2: Proposed Schedule of Completion

Appendix A: Draft Community Survey

Hello! I am a former Cleveland Park resident currently seeking my Masters of Urban and Regional Planning at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU). As part of my degree I am conducting a study, in partnership with Cleveland Park Smart Growth, which is examining the possibility of increasing the supply of housing in the Cleveland Park, Woodley Park, Van Ness and Forest Hills neighborhoods. These neighborhoods were chosen due to their proximity to a Metro station (being within a ½ mile) and having predominantly single-family zoning. This project is not affiliated with the District Office of Planning and the recommendations made are not official positions of the city.

The following survey is open to residents within the study area (see map below), which is defined as those census blocks that are within a ½ mile of the Woodley Park, Cleveland Park, or Van Ness Metro Stations. Your responses will be used to inform the planning process. All responses are anonymous.

[Study Area Map]

Survey Questions:

How long have you lived in the area (within ½ mile of the Woodley Park, Cleveland Park, or Van Ness Metro Stations)?

- 0-5 years

- 6-10 years

- More than 10 years

Do you own or rent your residence?

- Own

- Rent

How many people, including yourself, live in your household?

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5 or more

Are you interested in moving within the Study Area?

Y/N.

What factors are affecting whether you move?

Please selected all that apply:

- Rent prices

- House price

- Type of housing

- Availability of a unit/home

Are you concerned about being able to continue living in the Study Area?

Y/N

If yes, why?

Do you plan to age in place in your current residence?

Y/N

If so, do you have concerns about your ability to do so?

If you own your residence: If your younger self were trying to live in your neighborhood today, how likely do you think you would have been able to afford to live in the neighborhood, at today’s price?

- Very likely

- Somewhat likely

- Not too likely

- Not likely at all

- Unsure

How important is your neighborhood commercial area to you?

- Very/ I use it to meet most of my regular needs

- Somewhat/ I use it to meet some of my regular needs

- Not at all/ It does not meet any of my regular needs

How important is transit service in your neighborhood to you?

- Very Important/Rely on it or use it frequently

- Somewhat Important/Use it occasionally

- Not at all/Don’t use it

How important is environmental sustainability to you?

- Very

- A moderate amount

- Not very

How do you feel about the availability of housing that is affordable for all income levels?

- Too Much

- Just Right

- Too Little

Gentle density is the practice of building accessory dwelling units (ADUs), residential flats (single family structures that have been internally divided into individual units), duplexes, and small multi-family buildings (no taller than four stories) in areas which have historically been exclusively single-family homes.

Below are examples of Gentle Density. Please mark those which you would support being built in your neighborhood.

Small Multi-Family Building:

Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU):

Duplex:

Would you support changing District policies (i.e. zoning codes, setback requirements, etc.) to allow the types of housing you selected to be built within your neighborhood?

Y/N

Capstone Panel Members

Project Advisor: Dr. Niraj Verma, Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, Virginia Commonwealth University

Faculty Advisor: James Smither, Assistant Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, Virginia Commonwealth University

Professional Plan Client: Bob Ward, Chair, Cleveland Park Smart Growth

Works Cited

Accessory Dwelling Units. (n.d.). American Planning Association. Retrieved September 4, 2023, from https://www.planning.org/knowledgebase/accessorydwellings/

Affordable housing in opportunity areas or resource-rich neighborhoods. (n.d.). Local Housing Solutions. Retrieved October 25, 2023, from https://localhousingsolutions.org/housing-issues/affordable-housing-in-opportunity-areas-or-resource-rich-neighborhoods/

Alexander, G. J., & Williams, P. K. (2004). Woodley Park Historic District (A. Brockett, Ed.). D.C Historic Preservation Office.

Andersen, M. (2019, June 7). A Duplex, a Triplex and a Fourplex Can Cut a Block’s Carbon Impact 20%. Sightline Institute. https://www.sightline.org/2019/06/07/a-duplex-a-triplex-and-a-fourplex-can-cut-a-blocks-carbon-impact-20/

Baca, A., McAnaney, P., & Schuetz, J. (2019). “Gentle” density can save our neighborhoods | Brookings. Brookings Institution.

Baron Pollak, P. (1994). Rethinking Zoning to Accommodate the Elderly in Single Family Housing. Journal of the American Planning Association, 60(4), 521–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369408975608

Cherkasky, M., Shoenfeld, S. J., & Kraft, B. (n.d.). Mapping Segregation DC [Map]. Prologue DC. Retrieved November 1, 2023, from https://mappingsegregationdc.org/#maps

Connecticut Avenue Development Guidelines: Draft April 2023. (2023). District of Columbia Office of Planning.

“Connecticut Avenue Highlands” | The Cleveland Park Historical Society. (2011, December 6). https://www.clevelandparkhistoricalsociety.org/cp-history/connecticut-avenue-highlands/

Dear, M. (1992). Understanding and Overcoming the NIMBY Syndrome. Journal of the American Planning Association, 58(3), 288–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369208975808

Decision on Naming “A Restricted” Area in Zoning Deferred. (1923, October 27). The Washington Post.

Divounguy, O. (2023, June 22). Affordability Crisis: United States Needs 4.3 Million More Homes. Zillow. https://www.zillow.com/research/affordability-crisis-missing-homes-32791/

Doberstein, C., Hickey, R., & Li, E. (2016). Nudging NIMBY: Do positive messages regarding the benefits of increased housing density influence resident stated housing development preferences? Land Use Policy, 54, 276–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.02.025

Dunning, R., Hickman, H., & While, A. (2020). Planning control and the politics of soft densification. Town Planning Review, 91(3), 305–324. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2020.17

Ellickson, R. C. (2020). The Zoning Strait-Jacket: The Freezing of American Neighborhoods of Single-Family Houses. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3507803

Federal Highway Administration. (2013, January 31). Chapter 4: Actions to Increase the Safety of Pedestrians Accessing Transit. Pedestrian Safety Guide for Transit Agencies. https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/ped_bike/ped_transit/ped_transguide/ch4.cfm

Healey, J., & Ballinger, M. (2021, September 17). What just happened with single-family zoning in California? Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/homeless-housing/story/2021-09-17/what-just-happened-with-single-family-zoning-in-california

Historic Landmark and Historic District Protection Act of 1978: (D.C. Law 2-144, as amended through March 1, 2020), Pub. L. No. 2–144, § 6-1101 DC Official Code (1979).

Holleran, M. (2021). Millennial ‘YIMBYs’ and boomer ‘NIMBYs’: Generational views on housing affordability in the United States. The Sociological Review, 69(4), 846–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120916121

Housing Shortage Tracker. (2020, February 5). National Association of Realtors. https://www.nar.realtor/research-and-statistics/housing-statistics/housing-shortage-tracker

Kenworthy, J. R., & Laube, F. B. (1999). Patterns of automobile dependence in cities: An international overview of key physical and economic dimensions with some implications for urban policy. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 33(7–8), 691–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0965-8564(99)00006-3

Kim, J. (2016). Achieving Mixed Income Communities through Infill? The Effect of Infill Housing on Neighborhood Income Diversity. Journal of Urban Affairs, 38(2), 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12207

Lehning, A. J. (2012). City Governments and Aging in Place: Community Design, Transportation and Housing Innovation Adoption. The Gerontologist, 52(3), 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr089

Manville, M., Monkkonen, P., & Lens, M. (2020). It’s Time to End Single-Family Zoning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(1), 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1651216

Metrobus System Map. (2022). [Map]. Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority.

Morales, M. (2018a, June 20). If You Lived Here, You’d Be Home by Now: How Neighborhoods Can Kick Car Habits. Sightline Institute. https://www.sightline.org/2018/06/20/if-you-lived-here-youd-be-home-by-now-how-neighborhoods-can-kick-their-car-habits/

Morales, M. (2018b, July 18). Small Homes, Big Climate Dividends for Cascadia. Sightline Institute. https://www.sightline.org/2018/07/18/small-homes-big-climate-dividends-for-cascadia/

Nichols, J. L., & Adams, E. (2013). The Flex-Nest: The Accessory Dwelling Unit as Adaptable Housing for the Life Span. Interiors, 4(1), 31–52. https://doi.org/10.2752/204191213X13601683874136

Pfeiffer, D. (2015). Retrofitting suburbia through second units: Lessons from the Phoenix region. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 8(3), 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2014.908787

Reinink, A. (2012, November 16). Forest Hills, even the name is leafy. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/realestate/forest-hills-even-the-name-is-leafy/2012/11/15/cdc1d94e-2864-11e2-b4e0-346287b7e56c_story.html

Rock Creek West Roadmap. (2021). District of Columbia Office of Planning.

Rojc, P. (2017, March 12). In Appreciation of Gentle Density. https://www.planetizen.com/node/91658/appreciation-gentle-density

Scally, C. P., & Koenig, R. (2012). Beyond NIMBY and poverty deconcentration: Reframing the outcomes of affordable rental housing development. Housing Policy Debate, 22(3), 435–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2012.680477

Single Family Zoning in the District of Columbia. (2020). District of Columbia Office of Planning.

Stone, B., Mednick, A. C., Holloway, T., & Spak, S. N. (2007). Is Compact Growth Good for Air Quality? Journal of the American Planning Association, 73(4), 404–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360708978521

Vall-Casas, P., Koschinsky, J., Mendoza-Arroyo, C., & Benages-Albert, M. (2016). Retrofitting Suburbia Through Systemic Densification: The Case of the Metropolitan Region of Barcelona. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 33(1), 45–70.

Ward, B. (2022, January 20). Excluded from the Start: How Intentional Segregation Shaped Our Neighborhood. How We Got Here.

Whittemore, A. H., & BenDor, T. K. (2019). Exploring the Acceptability of Densification: How Positive Framing and Source Credibility Can Change Attitudes. Urban Affairs Review, 55(5), 1339–1369. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087418754725

Wicki, M., & Kaufmann, D. (2022). Accepting and resisting densification: The importance of project-related factors and the contextualizing role of neighbourhoods. Landscape and Urban Planning, 220, 104350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104350

Zoning Regulations of 2016 (Unofficial Version), (2016).