As the current debate over allowing the growth in Cleveland Park and other neighborhoods in Ward 3 reaches new levels of absurdity – as if Ward 3 was at risk of becoming gentrified – a look back at how the neighborhood came to be and sustained its exclusive nature is worthwhile.

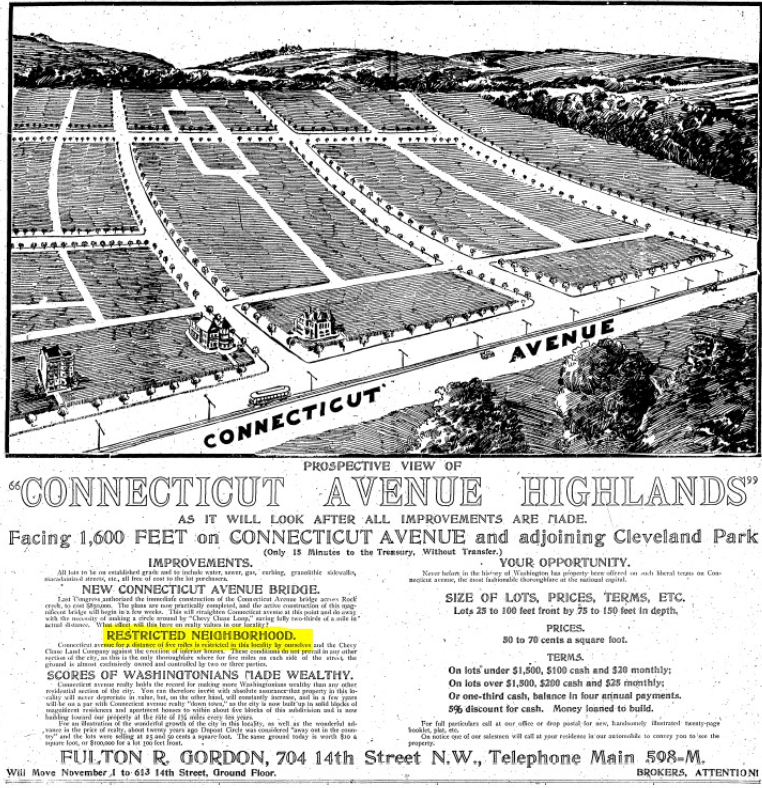

Cleveland Park, along with other neighborhoods in the area, were designed as segregated communities from the beginning. At the turn of the Twentieth Century, developers used land covenants to ensure homes built would price out poor residents. The Cleveland Park Company, and later developments like Connecticut Avenue Highlands, which advertised itself as “restricted,” required that homes built could cost no less than $5,000, a prohibitive sum for the working class of the day, and certainly out of reach to people of color. The Richmond Park development in the northwest part of the neighborhood, and later subdivisions around John Eaton School, ensured the growth of the neighborhood would be for Whites Only by adding racial covenants to the land deeds.

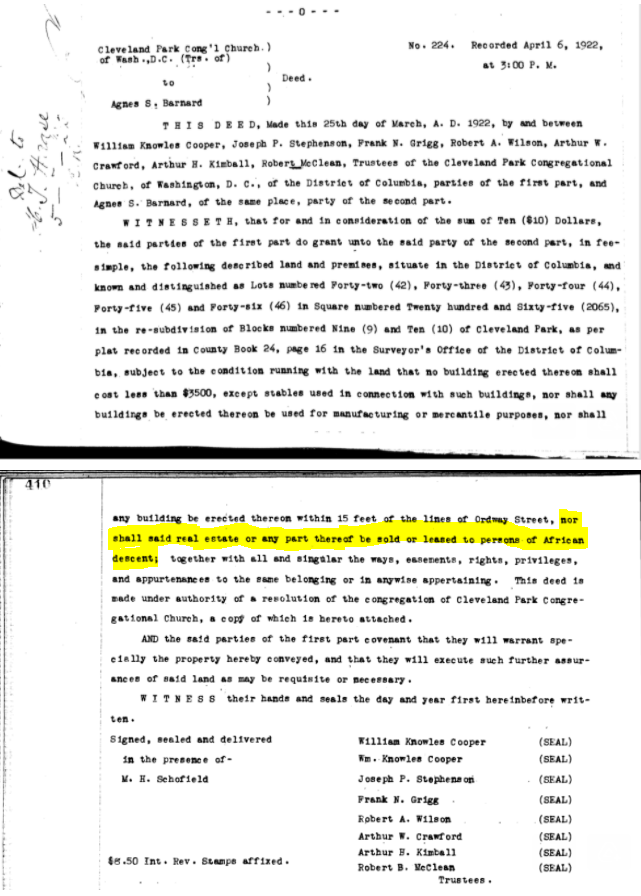

These deeds were so common even the local Cleveland Park Congregational Church kept them in the property they owned, as demonstrated by this sale of church property on Ordway Street in the 1920s:

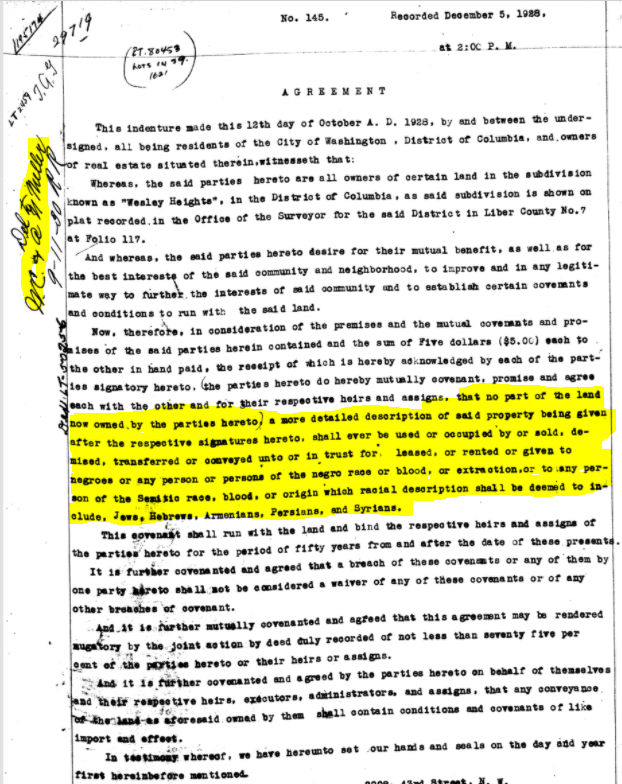

Not only was Cleveland Park founded with racist intent, it exported its racism to emerging neighborhoods in the vicinity. Local real estate magnates William and Allison Miller, who grew up on Highland Place, created the neighborhood of Wesley Heights, just south of American University. A pact was formed by the entire community to exclude not only Black people, but Jewish and a variety of other ethnicities.

Sadly, the impact of these restrictions were highly effective. In the 1940 census, the last before racial covenants were ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court, there was not a single Black homeowner in Cleveland Park. The handful of Black people who lived in Cleveland Park were the domestic servants living in the homes of their white employers, or the live-in janitorial staff of the area apartment buildings. As of the last census in 2010, the Black population of Cleveland Park (tract 6) was just 5%.

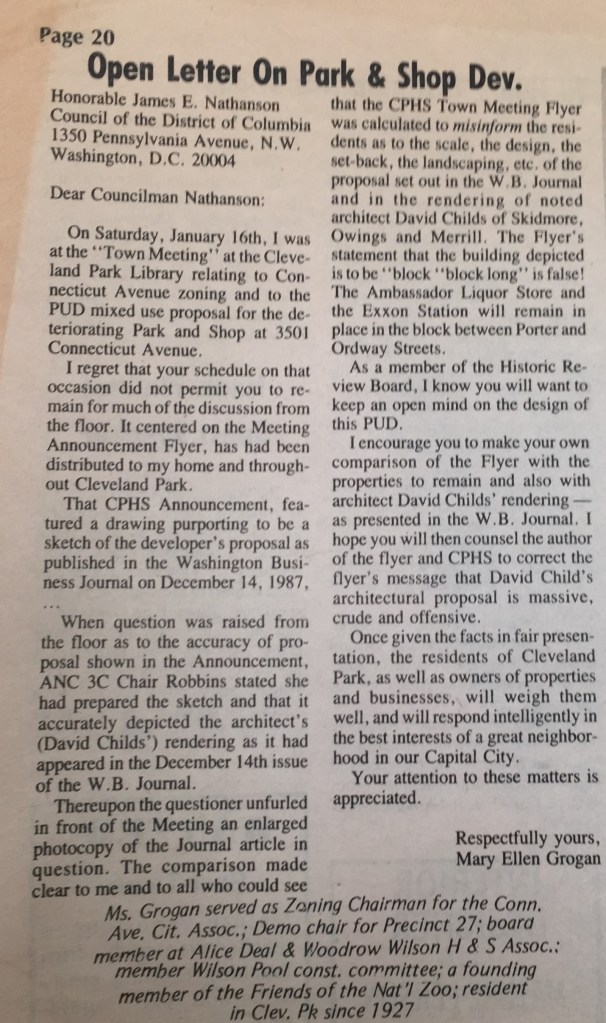

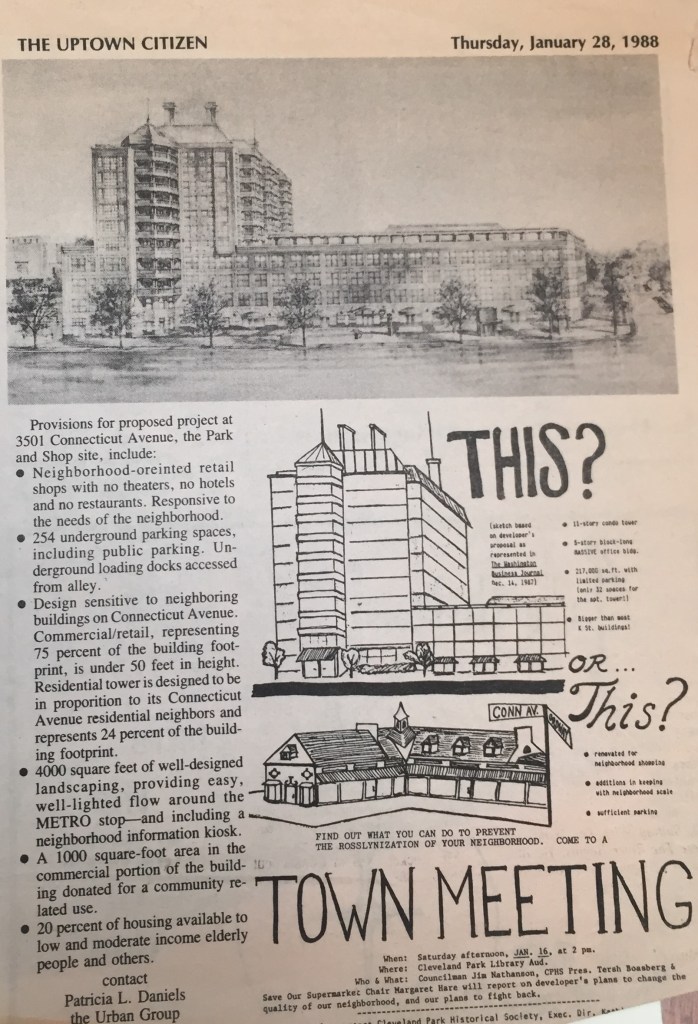

When the Metro finally came to Cleveland Park in the 1980s, a mixed use planned unit development was proposed to replace the Park and Shop. It was to offer a mix of retail, office and residential uses, a quintupling of parking over the existing surface lot, putting it underground, and 20% of the homes would be income-restricted. The local businesses were ecstatic. The area residents, not so much. The project was the catalyst that created the historic district, forever limiting the organic growth of the neighborhood. As one advocate told the Washington Post at the time, “Can an urban neighborhood control what happens to it, or is development inevitable?” indicating that the use of the preservation law was as much about a proxy for land use control as anything. These restrictions were not racial in motivation, but the effect was to impact the construction of more diverse housing.

Indeed, all around the neighborhood are examples of housing that are more affordable than the multi-million dollar single family homes. Nearly every side street has an example of a duplex or small apartment building — nearly all built in the 1920s or earlier. None of these low density, multi-family homes could be legally built today. And even if zoning allowed it, historic preservation would preclude substituting a single family home for a multi-family one.

Unwinding this history is likely impossible. As local realtor Casey Aboulafia noted during a recent ANC meeting, housing prices in the neighborhood are very high and have shown no signs of abating. She posted neighborhood housing price data on her Facebook page, “Average price of Detached homes in ONLY the last 10 years have increased from $1.33m to $2.040m – $710k increase. For Townhouses, it’s increased to $1.44m from $880k – $560k increase over the last 10 years. For condos, it’s gone up about $100k on average over the last 10 years from about $350k to $450k.”

Knowing this history makes it even more important that we look for ways to make living here more accessible to more people. We need to start the conversation about how we unwind some of the institutional road blocks that inhibit the production of lower cost homes, including zoning and overly restrictive historic preservation. To be sure, this is not a problem unique to Cleveland Park. But that it faces so many communities in the U.S. is also no reason not to start taking action here, now.

post script: It is frustrating to see not one word of this restrictive history in the nomination petition that created the Cleveland Park Historic District, and no subsequent work that I could find from within the neighborhood. I am a complete amateur on the historical research. The subject deserves more serious and complete study. The Mapping Segregation project is doing important work tracking racial covenants, but I realized they are very much a work in progress and that many of the restricted deeds I found were not yet on their records. My guess is that the original restricted deeds were included when the subdivisions were created, which predate the Recorder of Deeds online database. The latter goes back to 1922.

thank you for this. Just a really important bit of history that all of us in cp/wp need to keep in mind. It’s not history, after all, we’re still living it.

LikeLike

This article is really interesting. Information about history like this should be spread widely. It should be a part of the affordable housing conversations.

LikeLiked by 1 person